The spirit of the age has shifted. The six portrayed women will probably not be mention in the Chinese party-state's report on and celebration of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, Ming Li and Gordana Malešević conclude.

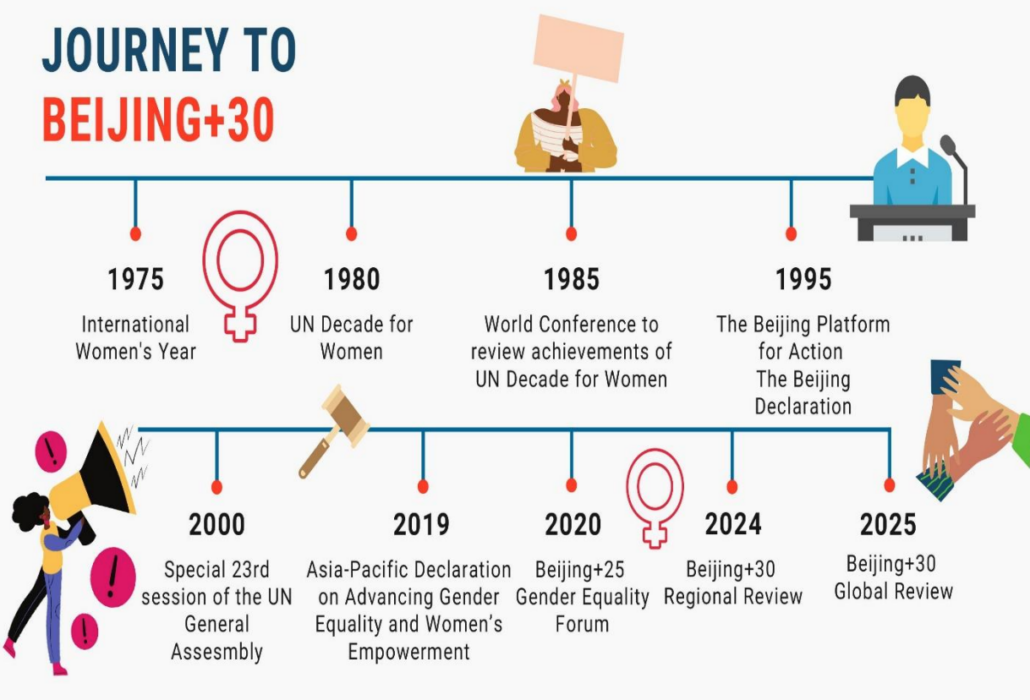

The Fourth World Conference on Women was the most important of the four conferences on women held between 1975 and 1995. It built on political agreements reached at the previous global conferences and consolidated five decades of legal advances aimed at securing the equality of women and men in law and practise.

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action was adopted unanimously by 189 countries. It is an agenda for women’s empowerment and is considered the key global policy document on gender equality. It sets strategic objectives and actions for the advancement of women and the achievement of gender equality in 12 critical areas of concern: poverty, education and training, health, violence, armed conflict, economy, power and decision-making, institutional mechanisms, human rights, media, environment, and the girl child.

In 2020, 25 years after the historic Fourth World Conference on Women, the UN Women Executive Director (2013–2021) Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka sent a message:

’In that quarter century we have seen the strength and impact of collective activism grow and have been reminded of the importance of multilateralism and partnership to find common solutions to shared problems.’

The reminder was needed, since a quarter of a century after the conference, no country was even close to fully delivering on the commitments of The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. In addition, the spirit of the age has shifted. Gender equality is questioned while autocracy, conservative values and patriarchy are surging worldwide. Authoritarian leaders are launching a simultaneous assault on women’s rights and democracy that threatens to roll back decades of progress on both fronts.

Thirty years after the adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, it remains a key milestone and a reference in the international and regional human rights agenda, guiding the development of regulatory frameworks and public policies that seek to advance gender equality.

Rahile Dawut, Agnes Chow, Guo Jianmei, Wang Yu, Xiao Meili and (Sophia) Huang Xueqin will probably not be mentioned in the Chinese party-state’s report on and celebration of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action.

Rahile Dawut

In March 2024, the Human Rights Committee of Sweden’s Scientific and Literary Academies once again urged the Chinese authorities to release Professor Rahile Dawut, an ethnographer, who is reportedly serving a life sentence in an undisclosed location.

‘Your Excellency,

We, the Human Rights Committee of Sweden’s Scientific and Literary Academies, contact you respectfully to express our concern about Professor Rahile Dawut, a Chinese ethnic Uyghur ethnographer who reportedly is serving a life sentence in an undisclosed location.

Professor Rahile Dawut is well-known and respected in the international scientific community for her scholarly work on Uyghur folklore and religious culture. It is our understanding that much of her academic research at Xinjiang University was funded by China’s Ministry of Culture and that she has been recognized by the government for her contributions to the study of Chinese folklore. Professor Rahile Dawut reportedly disappeared in December 2017. We are alarmed that, six years later — without any information made public about her legal status, whereabouts, or well-being — reliable accounts indicate that she is serving a life sentence in China for allegedly endangering State security. Given the secrecy surrounding her case, there is reason to believe that her right to a fair trial and the standards of due process of law have not been respected but violated in an alarming manner.

In light of the information above, it appears that Professor Rahile Dawut has been arbitrarily detained and denied access to due process. These rights are protected under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which China is a signatory. Thus, we respectfully urge you to use your good offices to ensure that she is immediately and unconditionally released from prison. In the interim, we ask for your assistance in disclosing her whereabouts and ensuring that her conditions of confinement are brought into conformity with the U.N. Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules), including that she is allowed regular access to her family, to legal counsel, and to any needed medical care.

Thank you, Your Excellency, for your attention to this important matter.

Respectfully yours,

The Human Rights Committee of Sweden’s Scientific and Literary Academies

The Human Rights Committee of Sweden’s Scientific and Literary Academies includes members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities, the Swedish Academy and the Young Academy of Sweden.’

Agnes Chow

In 2014, Agnes Chow Ting worked with student organizations to advocate for electoral reform in Hong Kong. She was a leader of the class boycott campaign against the restrictive electoral framework set by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee for the 2017 Chief Executive election in Hong Kong, which led to the massive Occupy protests called the ‘Umbrella Revolution’.

Chow is, together with Joshua Wong and Nathan Law, the co-founder of the political party Demosisto and former spokesperson of Scholarism. Her candidacy for the 2018 Hong Kong Island by-election, supported by the pro- democracy camp, was blocked by authorities, due to her party’s advocacy of self-determination for Hong Kong. Agnes Chow was arrested in August 2019 for allegedly participating in and inciting an unauthorised assembly at Hong Kong Police Headquarters 21 June 2019. She was released the same day on bail, but her smartphone, like those of her fellow arrestees, was confiscated by the police.

Following the enactment of the National Security Law by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, Chow was arrested again on the charge of ‘collusion with foreign forces’ in August 2020 and released on bail the day after. On 2 December 2020, she was sentenced to ten months in jail. On 12 June 2021 Chow was released from prison.

On 3 December 2023, Agnes Chow Ting made her first public announcement on social media since her release saying that she had ‘moved to Canada in September 2023 to study for a master’s degree at University of Toronto’. Police had returned her passport after she had agreed to travel on a police-escorted tour to Shenzhen. She also wrote, ‘I was originally scheduled to return to Hong Kong at the end of December and report to the police in compliance with the National Security Law. After careful consideration, including with regards to the situation in Hong Kong, my own safety, and my physical and mental health, I have decided not to go back to reporting, and I probably will never go back in my life’.

Secretary for security in Hong Kong, Chris Tang, commented that ‘Chow’s behaviour might affect other arrested suspects who are showing genuine remorse and earnestly trying to turn over a new leaf’.

Guo Jianmei

Guo Jianmei is a lawyer and human rights activist. In 1995, she attended the Fourth International Forum for Women Lawyers and the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. Later that year, she co-founded the Beijing University Law School Women’s Legal Research and Services Centre, the first non-profit, non-governmental organisation (NGO) specialised in safeguarding the rights and interests of women. She has held roles at the Ministry of Justice, the All-China Women’s Federation and the All-China Association of Lawyers. Guo also participated in a revision of the Marriage Law in 2001 and the enactment of the Regulations for Legal Aid in 2003. A prolific author, Guo has published eight books and is the editor of three volumes of popular legal guides, including ‘Everyday Life Law’ and ‘A Guide to Women’s Legal Aid Cases’.

In 2010, Guo was awarded the Simone de Beauvoir Prize and was announced as China’s first anti-AIDS discrimination ambassador by the International Labour Organization (ILO). The same year, Beijing University officially disassociated itself from the Beijing University Law School Women’s Legal Research and Services Centre, and in 2016 authorities ordered the center to close.

In 2019, Guo received the Right Livelihood Award ‘for her pioneering and persistent work in securing women’s rights in China’. The Right Livelihood Award is widely known as the ‘Alternative Nobel Prize’ and celebrated its 40th anniversary in the year of Guo’s reception. In its press release, the Right Livelihood Foundation stated:

‘Guo Jianmei is a pioneer of women’s rights. She has provided legal support to thousands of Chinese women and demonstrated how the law can be used to successfully fight gender discrimination.

Guo consistently addresses gender bias in the justice system and helps raise gender awareness in China, a country with around 650 million women. She has founded and directed one of the most impactful non-government organizations for the protection of women’s rights. As China’s first public interest lawyer dedicated to providing legal aid on a full-time basis, Guo successfully introduced the concept of pro bono legal services for marginalized persons into the Chinese context. Since 1995, she and her team of lawyers have offered free legal counselling to more than 120,000 women all over China and have been involved in more than 4000 lawsuits to enforce women’s rights and advance gender equality.

Guo Jianmei’s work shines a spotlight on the state of women’s rights in China, where one in four married women have experienced some form of domestic violence at the hands of a husband, and gender discrimination at the workplace is rampant. Guo guides women through lawsuits and carries out legal advocacy at a national level on issues like unequal pay, sexual harassment, work contracts that prohibit pregnancies and forced early retirement without compensation. In rural China, where patriarchal attitudes are still deeply rooted, Guo provides legal support for women who have been denied their land rights. In 2005, she created the China Public Interest Lawyers Network that gathers more than 600 not-for-profit lawyers who can take up cases even in remote regions of China. Together with colleagues, she has also provided a vast number of legal commentaries and research findings that have led to the refinement and improvement of relevant laws and regulations. In the face of a dramatically shrinking space for civil society in China, Guo Jianmei has shown courage and extraordinary resilience. Her work continues to impact the lives of millions of Chinese women.’

Wang Yu

Wang Yu was a business and commercial lawyer until an incident at a Tianjin train station in 2008. At that time, she had an argument with railway employees because she was denied entry onto a train despite holding a valid ticket. In a peculiar turn of events, filmed and published on social media by several shocked bystanders, Wang was arrested, charged with ‘intentional assault’ and imprisoned for more than two years. While in prison, she learned how prisoners were mistreated and tortured. Upon her release in 2011, she began work as a human rights lawyer.

Wang represented several prominent cases, including the well-known Uyghur intellectual and professor of economics Ilham Tohti, who was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2014 on charges of separatism – charges that contradicted his actions and published work. Wang also served as a lawyer for the feminist activist Li Tingting. In 2013, Wang travelled to the southern island of Hainan to provide legal assistance to the families of six schoolgirls who had allegedly been sexually abused by their school principal. On 9 July 2015, Wang, along with approximately 300 other human rights lawyers and activists, was arrested in a nationwide police raid. Until her official detention in 2016, she was held under ‘residential surveillance at a designated location’. She was not permitted access to a lawyer, nor were her whereabouts confirmed by the police.

This practice (referred to as ‘residential surveillance’) was allowed at the time under Article 73 of the Criminal Procedure Law which permitted the detention of suspects in state security, terrorism and serious bribery cases for up to six months in undisclosed locations. Authorities were not obliged to specify the place of detention or notify the suspects’ relatives or legal representatives if doing so may ‘interfere with the investigation’. In June 2015, Xinhua published a piece designed to tarnish Wang Yu’s reputation, describing her as an ‘arrogant woman with a criminal record turned overnight into a lawyer’. This campaign was followed by a smear campaign in China’s official media and on social media platforms.

In October 2015, Burmese police detained human rights defenders Tang Zhishun and Xing Qingxian, along with Wang Yu’s son, Bao Zhuoxuan. In 2016, authorities released Wang Yu on bail after she gave a televised confession denouncing her colleagues and claiming that her human rights work was influenced by foreign activists’ intent on smearing China. Her televised confession followed a pattern similar to those given by other lawyers, publishers and human rights activists. In 2016, a jury composed of 22 European lawyers from the bars of Paris, Bordeaux, Amsterdam, Berlin, Brussels, Geneva, Luxemburg and Rome, together with European Bar Human Rights Institute (IDHAE) and the Union Internationale des Avocats (UIA) awarded Wang Yu the prestigious 21st Ludovic Trarieux International Human Rights Prize. In choosing Wang, the jury wanted to ‘hail the courage’ of a woman who ‘decided that she could no longer keep her mouth shut despite the danger of speaking out and chose to expose herself to dangers in order to defend the rights of women, children and persecuted minorities.’ Wang’s license to practice law has been revoked, and she is barred from applying for a passport or traveling abroad. Despite this, she continues to handle legal cases and gives legal advice as a so-called ‘citizen lawyer’.

Xiao Meili

In response to several sexual assault and physical abuse cases involving primary school children in 2013, Xiao Meili set out on a 2,000 km walk through five provinces from Beijing to Guangzhou to raise awareness of sexual assault and to change victim-blaming tendencies. The walk lasted from September 2013 to March 2014 and intended to reclaim public roads as a safe place for women and contest the implication that women should stay indoors to avoid sexual abuse. In each city she passed, Xiao Meili gathered signatures and sent letters to local officials to advocate for better safety and sex education, more support for sexual assault victims, vetting processes for teachers, and improved measures for preventing sexual assault, especially concerning children. For the 165 letters Xiao Meili sent, she received more than 2,000 signatures and replies from local governments promising action. Xiao Meili received several requests for interviews and public talks to share her messages and earned the support of residents who joined her for portions of the walk, offered accommodations, and donated money.

Xiao Meili began advocating for gender equality in 2012. Her first campaign was on Valentine’s Day. Together with two friends, she protested against domestic violence by parading down a famous pedestrian street in Beijing wearing wedding dresses smeared with fake blood and holding signs such as ‘love is not an excuse for violence’ to denounce violence in intimate relationships. On 30 August 2012, Xiao Meili and three friends, including Li Tingting (also known as Li Maizi) and Liang Xiaowen, shaved their heads in public to protest the lower college entrance exam scores required for male students compared to female students for admission into certain programs.

In early 2018, Xiao engaged in activism to address sexual harassment of women on public transportation. She cited Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex as a strong influence in shaping her activist work. During China’s #MeToo movement, Xiao played a major role both as an activist and a spokesperson for sexual assault survivors.

In June 2019, Xiao Meili, Zhang Leilei and Tian Zuoyi hosted a podcast titled ‘A Little Pastoral’ (有点田园). They spoke about gender and feminism, mainly focusing on personal stories and cases in the news. The podcast had reached 25,000 listeners at the beginning of 2020.

In 2021, Xiao and several other feminist activists experienced online bullying by anti-feminists. Xiao was also a target of doxing – the act of publicly providing personally identifiable information about an individual without their consent. A Weibo user with more than 700 000 followers, known for his nationalist stance, accused Xiao of supporting Hong Kong’s independence, citing a photo posted several years earlier. The incident resulted in several of her social media accounts being shut down.

(Sophia) Huang Xueqin

(Sophia) Huang Xueqin, a leading voice in China’s feminist movement, began her career as an investigative reporter in Guangzhou before shifting to freelance journalism. At her first job in a national news agency, she was sexually harassed by a senior reporter, which compelled her to leave. In 2016, after learning about the similar experience of a female colleague, Huang recognized the urgency of uncovering women’s stories of sexual harassment that were long underreported in mainstream media. She used her journalistic skills to engage in political activism and amplify the voices of women silenced by institutional complicity. In 2017, she assisted Luo Xixi, a former graduate student of Beihang University, in disclosing and denouncing a professor’s sexual misconduct on social media. This collaboration marked a pivotal breakthrough in China’s grassroots campaign against gender-based violence, which had been forcefully curtailed by the state’s 2015 crackdown on feminist activism. That same year, Huang conducted a groundbreaking online survey of hundreds of women news workers and published a report in 2018, revealing that 83.7 percent of women had experienced some form of sexual harassment in the newsroom. The exposure galvanized the domestic #MeToo movement in dialogue with global feminist mobilizations, empowering many others to confront injustice, speak out, and raise public awareness of gender discrimination and sexual violence across industries.

In 2019, (Sophia) Huang Xueqin turned her journalistic focus to the political upheaval in Hong Kong, publishing first-hand accounts as both witness and participant in the anti-extradition movement. Her reporting quickly drew the ire of mainland authorities, who arrested and detained her for three months on charges of ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’. Though released on bail in early 2020, she was barred from leaving China. Despite ongoing surveillance and police harassment, Huang continued her political activism. In September 2021, a day before departing for graduate studies in the UK, she and labour rights advocate Wang Jianbing were forcibly disappeared and later charged with ‘inciting subversion of the regime’, for allegedly organizing unlawful gatherings to share anti-government writings. After a secret trial in Guangzhou, Huang was sentenced in June 2024 to five years in prison. Supporters note that she firmly pleaded not guilty, upholding her political integrity and refusing to concede under state repression.

Huang embodies the ongoing struggle for press freedom. Her legacy continues to inspire cross-movement organizing among feminist, LGBTQ, labour and pro-democracy communities, and fuels transnational solidarity beyond mainland China.

Ming Li — educator and scholar.

Gordana Malešević — political scientist and editor of the forthcoming anthology Challenges for Chinese Women in the Early Twenty-First Century